🩹 Designing primers for rapid skin pathogen detection

Designing and testing RPA/PCR primers for point-of-care diagnosis of skin infections

💡 An idea for faster skin infection diagnosis

Our colleagues at the National Institute for Research and Development in Microtechnologies (IMT Bucharest) had a brilliant idea - leveraging an isothermal amplification method, specifically the Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA), in a Point-Of-Care device. The beauty of RPA is its potential to work at a pretty low temperature, which got us thinking – could we even use body heat to drive the reaction? This thinking laid the groundwork for aiming towards an interesting concept: a diagnostic ‘band-aid’ that could identify pathogens in skin lesions, and we even got to present our work at AMLR 2024.

🧬 Good moment for me to learn how to design primers

Did my homework and scoured the interwebs for how to do it properly, and also had a good bunch of guidance from other senior lab colleagues. Before jumping into design, I set some ground rules for what makes a good RPA primer, drawing from established guidelines:

- Length: 27-35bps for RPA, 18-24bps for PCR

- GC Content: Less than 70% for RPA, 40-60% for PCR

- Melting Temperature (Tm): A broad range of 0-80°C is often cited for RPA, though we aimed for practical Tms, and 66-68°C for PCR

- Amplicon Size: 100-300bps

- Secondary Structures: We wanted to avoid primers that liked to stick to themselves. Specifically, aiming for a self-complementarity score <8 and a self 3’ complementarity score <3.

- Dimers: No self-dimers or cross-dimers with other primers in the mix.

🎯 Targets and tools

I focused on three key microorganisms: Haemophilus influenzae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Aspergillus fumigatus. For each, I selected a specific target gene based on existing research that showed its suitability for species-specific detection.

- For Haemophilus influenzae the target I used was the OmpP6 gene seeing how it was previously used in other studies. It’s present in all H. influenzae strains and has a highly conserved nucletoide sequence with a very good homology rate, making it a great target gene for microbial specificity.

- For Pseudomonas aeruginosa, I targeted the oprL gene, which codes for an outer membrane lipoprotein. This gene is known for its high specificity to P. aeruginosa and has been successfully used in other detection studies.

- For Aspergillus fumigatus, the target was the rodA gene. It’s involved in producing the hydrophobin RodA, a key component of the fungal cell wall, and its specificity to A. fumigatus has been established in previous research, making it a good candidate for our detection assay.

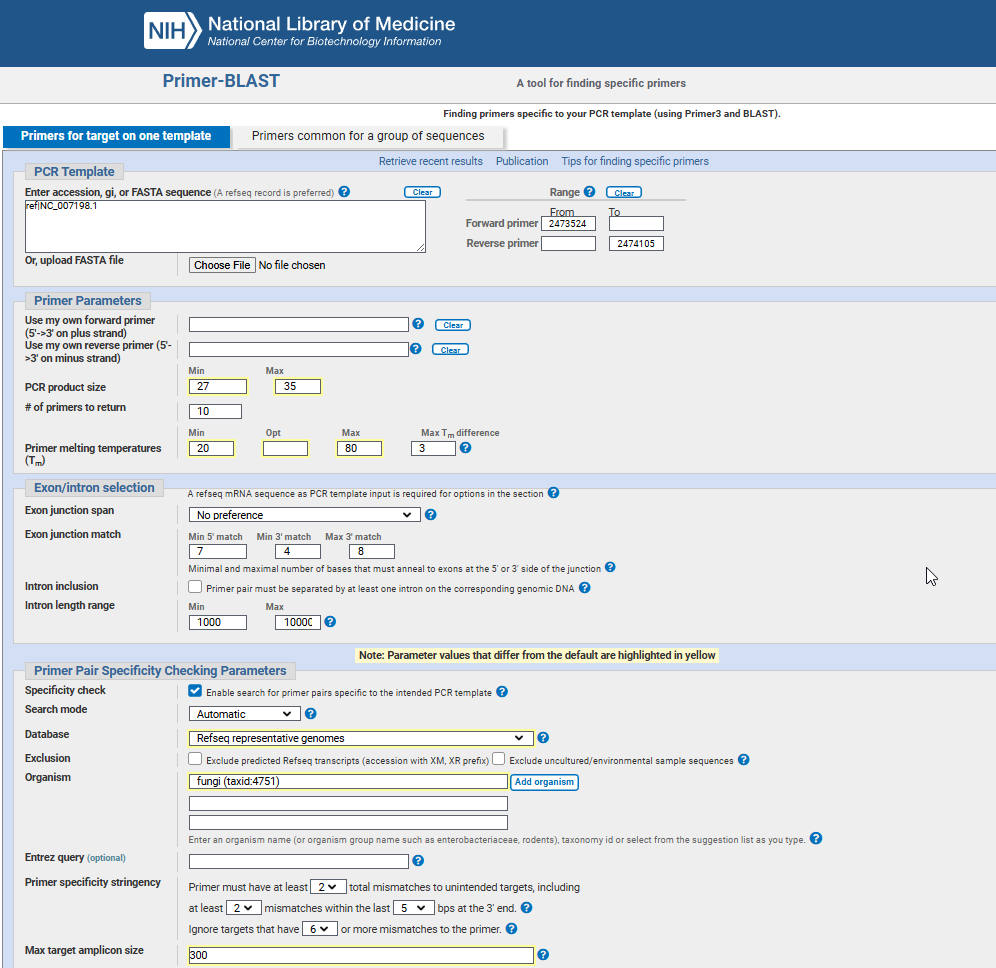

I used NCBI’s Primer-BLAST as the primary tool for getting primer candidates, using the ground rules previously mentioned. Database used was initially “nt”, being the most comprehensive one, with the broadest possible checks against known sequences. It is a bit too large and can include redundant sequences or partially sequenced genomes, but I wanted to make sure and I could filter out the results afterwards. I also tried and eventually settled on using the “RefSeq representative genomes” for more specify searches. Very important was the “Organism” field which had to have bacteria (taxid:2) or fungi (taxid:4751) as domains, for the specificity checks.

To avoid issues where primers might fold up on themselves or stick to each other (forming secondary structures), I double-checked our primer pairs using SMS’ Primer Stats.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

Single base runs: Pass

Dinucleotide base runs: Pass

Length: Pass

Percent GC: Pass

Tm (Nearest neighbor): Warning: Tm is greater than 58;

GC clamp: Warning: There are more than 3 G's or C's in the last 5 bases;

Self-annealing: Pass

Hairpin formation: Pass

And then stick them into Thermo Multiple Primer Analyzer to get additional properties like Tm, GC% content, molecular weight, primer-dimer estimation, etc

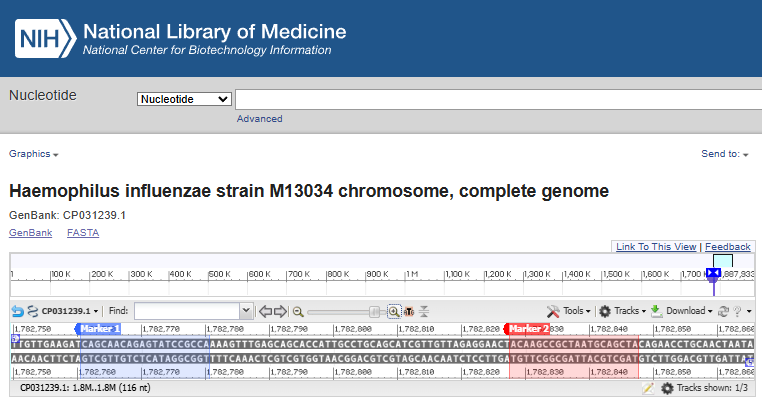

After narrowing down to a few pairs I started reverse checking them using NCBI Blast to make double sure they don’t “stick” to other organisms as well as to visualise the target area in the genome viewer.

H. influenzae’s forward and reverse PCR primers in the genome viewer

H. influenzae’s forward and reverse PCR primers in the genome viewer

Eventually, after lots of trial and error and multiple Primer Blast runs, I settled on 6 of them - 3x PCR primer pairs and 3x RPA primer pairs.

| Microbial Species | Target Gene | Primer Details (5’ to 3’) | Amplicon (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H. influenzae (Hi) | OmpP6 | RPA F: GGTTTTGATAAATACGACATTACTGGTGAA RPA R: AACACCTTTACCTGCTAAATAACCTTTAACT | 195 |

PCR F: TAGCTGCATTAGCGGCTTGT PCR R: CAGCAACAGAGTATCCGCCA | 87 | ||

| P. aeruginosa (Pa) | oprL | RPA F: CACCTTCTACTTCGAGTACGACAGCTCCGAC RPA R: CTCTTTACCATAGGAAACCAGTTCCAG | 244 |

PCR F: CTTCGAGTACGACAGCTCCG PCR R: CCTTTCAGGTCTTTCGCGTG | 75 | ||

| A. fumigatus (Af) | rodA | RPA F: GACATATCTTAGTCCCCATCATTGGTATTC RPA R: GAACTACAAATATATAGAGGAACACTTACGG | 130 |

PCR F: GTTCCTGACGACATCACCGT PCR R: TGGAGCACTGGTTGAAGAGAC | 193 |

💧 DNA extraction & results

With primer candidates designed, I needed DNA from the actual microbes. Our friends at the National Institute for Research and Development in Microbiology and Immunology “Cantacuzino” gave us some test subjects and I started working. I used the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification kit from Promega. The kit uses a slightly different approach depending on the bug: Gram-negative bacteria were lysed by incubating them at 80°C, while Gram-positive bacteria and fungi needed a bit of enzymatic lysis to break them open - lysozyme and lyticase, respectively.

| Microbial Species | DNA Concentration | 260/280nm Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| H. influenzae | 335 ng/µL | 1.84 |

| P. aeruginosa | 166 ng/µL | 1.97 |

| A. fumigatus | 21 ng/µL | 1.92 |

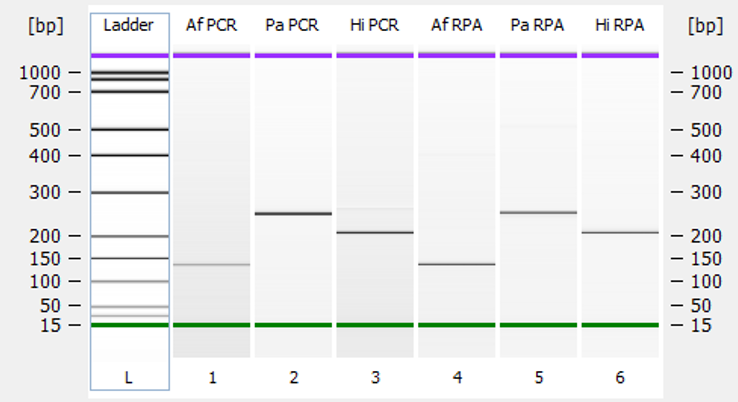

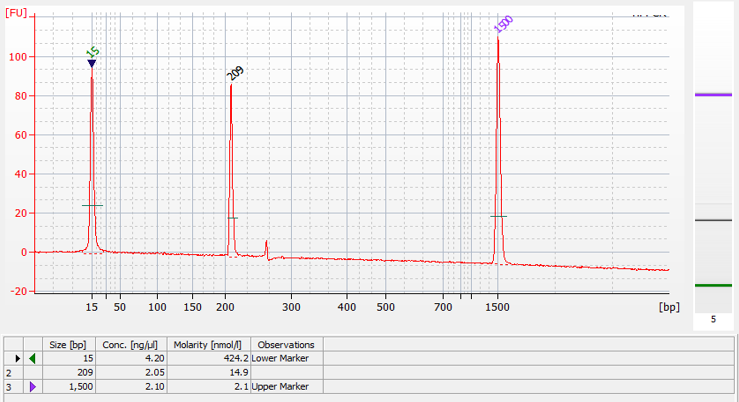

Next up, we had to see if the designed primers actually worked! Our IMT colleague, Melania helped us with the liquid-phase RPA reactions. To really be sure about their specificity, we also ran standard PCR reactions using the PCR primer sets. This allowed us to compare the results. After this we had to check the results using microfluidic capillary gel electrophoresis. We saw amplicons of the expected sizes in both RPA and PCR, with no signs of non-specific amplification. Success!

Then came the adaptation to a solid support. The brilliant technicians at IMT Bucharest took this entire effort into their hands, and the results of their work were absolutely amazing. They made a biochip using silicon wafers and used a cool technique called Metal-Assisted Chemical Etching (MACE) to create silicon nanowires on the chip’s surface in order to massively increase the active surface area available for attaching our forward primers.

These forward primers were designed with an amino group added to their 5’ end, allowing them to bind to the silane-coated silicon surface of the biochip. In the reaction mix that went onto the chip, we only included the reverse primers, which were modified with a Cy3 fluorescent label. This label would let us see if amplification happened.

Melania used PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane - a silicone polymer) to create tiny wells on the biochip where the RPA reaction would take place. The reaction conditions were the same as in the liquid phase tests: 20 minutes at 39°C (nicely close to body temperature). After the reaction, the wells were thoroughly washed with deionized water to remove any unbound reagents.

PDMS wells on top of the silicon wafer

PDMS wells on top of the silicon wafer

🔬 Confocal microscopy visualisation

To see if the solid-phase RPA worked, we used a Carl Zeiss LSM 710 Confocal Microscope. This gave us a detailed picture of where the Cy3 fluorescence was located in the well and how intense it was. We could see that the increased surface area from the nanowires positively influenced the binding of the amplicon. Compared to a negative control (which was completely colorless after washing), the wells where amplification occurred showed significant fluorescence. This confirmed that our solid-phase RPA was a success.

H. Influenzae reaction visualisation (Objective 20x/0.50 M27, Pinhole 52µm, Excitation wavelength 514nm)

📔 2024 AMLR conference

I was also really proud to present this research and our findings at the AMLR (The Romanian Association of Laboratory Medicine) conference in 2024. It’s always great to share your work with peers. On top of that, this study was also published in the Romanian Journal of Laboratory Medicine (read it here, on page 74).

It’s fantastic to see collaborative projects like this, bridging bioinformatics, wet lab and microtechnology to contribute to the field of diagnostics. This was a really fun project and I definitely learned a lot.